.jpg)

Temitope Felicia Odu, 56, had only just been called to the Nigerian Bar in September 2025. Photographs from the ceremony show her smiling beneath her wig, surrounded by congratulatory messages and the quiet pride of a long-awaited achievement. It was the beginning of a new chapter.

Weeks later, on Oct. 14, she was reportedly found dead in her home in Ikorodu, Lagos. Accounts shared by colleagues suggest she may have been strangled. Her husband was said to be linked to the incident, which allegedly occurred in the presence of their child, according to Punch.

What remains undeniable is this: a colleague, a mother, and a newly minted lawyer is gone.

What is clear is devastating. A woman died suddenly and violently. Everything else must move carefully from allegation to fact.

That process matters. Preserving the scene, conducting a professional autopsy, and building a credible timeline are not technical formalities. They are the foundation of justice. Nigeria’s Constitution guarantees the right to life and due process, and those guarantees demand restraint, evidence, and clarity before conclusions are drawn.

Rumors cannot substitute for proof. Only a thorough and lawful investigation can.

The questions many are asking are simple and logical:

-

Is this country safe for women inside their own homes?

-

If something like this happens, what does the law do immediately?

They are reasonable questions a society must confront when a life ends under contested circumstances. When institutions respond transparently and lawfully, public trust grows. When they do not, suspicion fills the silence.

Justice that endures is built on patience and proof. An evidence-driven investigation serves everyone involved: the deceased, the public, and even the accused, who remains entitled to the presumption of innocence until a court decides otherwise.

Under Nigerian law, the burden of proving a criminal offense rests squarely on the state and must be established beyond a reasonable doubt. That standard protects against error, vengeance, and irreversible harm.

Anything less diminishes justice for all.

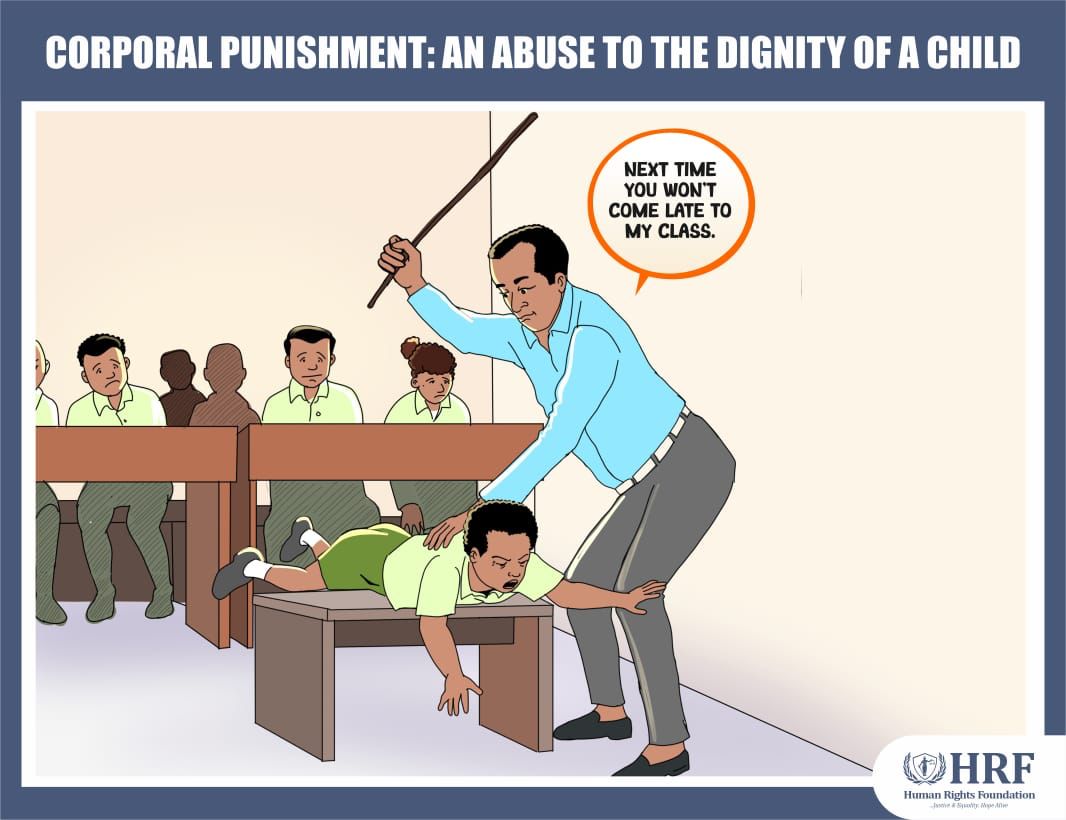

Temitope’s death also sits within a troubling and familiar pattern. Many women face the greatest danger not in public spaces, but in their own homes.

Lagos State’s Protection Against Domestic Violence Law, enacted in 2007, allows survivors — and even concerned third parties — to seek protection orders and urgent legal relief. The law exists to prevent tragedy, not merely to respond to it. Rights, as the legal maxim reminds us, must come with remedies. But Temitope must not be reduced to a statistic. She was a person with a name, a family, a profession, and a future that had just begun to take shape.

For members of the legal profession, this loss cuts especially deep. Temitope had only just joined the ranks she had worked so hard to enter. Her death is not only a personal tragedy but a reminder of the profession’s deeper calling.

Law is more than statutes and courtrooms. It is a promise — about fairness, dignity, and protection when it matters most. The old maxim fiat justitia ruat caelum — let justice be done though the heavens fall — calls on institutions not to look away.

Temitope pledged to uphold justice. In her name, the institutions she served owe her — and the public — a credible investigation, lawful oversight, and outcomes grounded in truth.

.jpg)

0 Comments